Earlier this year, the Johns Hopkins Center for American Indian Health announced the launch of an initiative to address breast, colorectal, and stomach cancers with tribal communities in the Southwestern U.S.

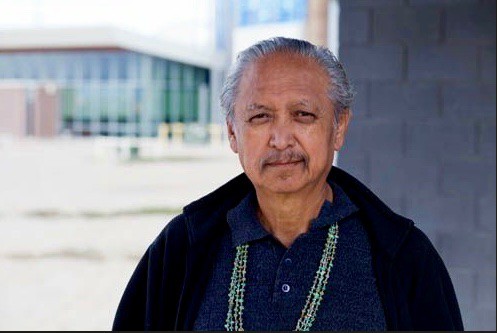

The Center is excited to be working with cancer epidemiologist Dr. Marc Aaron Emerson (Navajo) to understand the barriers to accessing cancer care in rural tribal communities. Dr. Emerson, who recently earned a doctorate in epidemiology from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, was recently a Susan G. Komen trainee in the Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center focusing on breast cancer mortality disparities. He earlier held a Cancer Research Training Award Fellowship in the Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences of the National Cancer Institute.

Here is an excerpt from a recent conversation with Dr. Emerson:

What will you be doing with the Center’s cancer care project in the Southwest?

I will be traveling to communities to explore what barriers to cancer screening and care people are experiencing—developing interview and focus group guides, facilitating discussions, and analyzing the results. I will look for opportunities to improve the continuum of care for people suffering from common cancers in these communities, which are pretty isolated and underserved.

The Center is excited to welcome you back.

I originally worked at the Johns Hopkins Center for American Indian Health back in 2005 as a Diversity Summer Intern (I was an undergraduate at San Diego State at the time). I learned so much working on Family Spirit with Allison Barlow and John Walkup, under Mathu Santosham, who was the Center’s director at the time. The exposure to population-based health research—and the Center’s strong community-based participatory research model—was a core formative opportunity that led me to pursue a masters and doctoral degree in public health.

What kinds of research interests have you pursued recently?

My overall focus has been health disparities. My dissertation looked at health inequity in cancer as it relates to younger black women in the south. Socioeconomic and access to care disparities result in treatment delays. But poorer outcomes are also related to social constructs of race, the lived experience of black women, as well as biological predispositions to more aggressive cancers.

And you are seeing similar factors at play in Native communities?

It’s appalling that while certain cancer mortality rates for other groups are decreasing, the same cancer mortality rates are increasing for Native peoples.

I’m seeing disparities at play even in urban Indians communities. For those living in northern California, despite equal access to preventive services and cancer care, we found higher rates of death for American Indian people than non-Hispanic Whites with some cancers and a greater proportion of Native cancer patients with multiple comorbid conditions.

What personally motivates you to work on this issue?

My father, Dr. Larry Emerson, was diagnosed with late stage stomach cancer during my fourth year of doctoral study at UNC. It was a very difficult time.

I moved home to our farm, Tse Daa K’aan, near Shiprock, NM, to be a caretaker. He would have to travel over 300 miles to his surgical appointments and follow up visits and 30 miles to his chemo appointments, which were pretty often. These are delays that can compound through the cancer continuum.

Accessing cancer screening, first of all, is critical. Having an earlier detection time is paramount in these windows in the continuum. Then you’re trying to access care in time to slow cancer’s growth or the spread. I saw those things up close.

My father was very important in my life. He was a scholar and social activist who lectured around the U.S. on language revitalization and Diné centered decolonization practices. He encouraged me to pursue western education while affirming my indigeneity and my Native identity.

He passed away from his cancer. Now, I’m even more driven to better understand how we can overcome these barriers, which are generalizable to Native people in many reservation-based communities, to detect cancers sooner and help more people survive.